Partner spotlight: Sidecar Creatives

Building unique spaces means there’s no playbook. It takes creative and flexible people teaming up to make something cool happen. Sidecar Creatives is one of those teammates we’ve worked with on several projects. We recently talked with Brianne DeRolph at Sidecar about our process together, using the recently completed Yokoso Cultural Center as the backdrop.

How do you approach a project?

Killian and I come from a retail design background so that’s how we were introduced to the field of design. Everything was always about the journey and the experience through a space. We do look at layouts; we do look at finishes. But everything is through the lens of how you’re taking a journey through a space – what you’re experiencing and key moments that might really differentiate that concept from something that you could get down the street elsewhere.

Thinking of it experientially, some of that doesn’t translate to design. Some of it doesn’t translate to a floorplan. It might be part of a business model. It might be something unique that is offered on site that doesn’t change the design at all. When we’re thinking through a concept, it’s more than just applying finish to a space. It’s also how it’s going to operate.

With the Cultural Center, that’s where we started. It was really immersive with the client. They were very involved. In naming exercises, figuring out what is the overall offering at Yokoso, they’re pretty hands-on and participatory. In the long run, because of their attention to minute details, it ends up being an even better finished product. It’s a very cool relationship that we have with them.

How do you use visual concepts to guide a project?

With Yokoso, we went through a pretty rigorous naming exercise. We went through tons and tons of options and continuously narrowed that down.

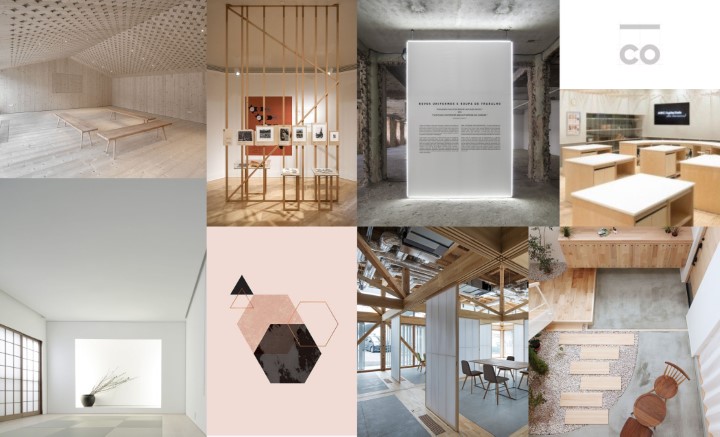

Concept One presented to Yokoso

In parallel with that, we’re also coming up with visual concepts for how this space could potentially look. Most of the time we’d deliver two or three concepts to our clients that are intentionally very polarizing from one another.

Concept Two presented to Yokoso

It can be a spectrum. These are wildly different from one another and maybe there’s something in the middle ground.

Concept Three presented to Yokoso

The purpose is to see which way the client is gravitating. That will help us be able to say, “Okay we need to be somewhere in this realm,” but also we can grab pieces from these other concepts and bring it over until it creates what we’d call a North Star to where we want to go.

So that’s just imagery. People call them mood boards – visual stuff, typically indicative of finish, style, vibe, lighting, everything like that.

A lot of times Killian will come in and layer on color theory. What type of colors should we use with a concept like this? What could potential names be for this? What are the patterns and photography styles?

That’s usually where we start: trying to get agreement between us and the client on this is the route we’re liking and this is where we want to go. That’s when we put pen to paper and start looking at the space and space planning.

Collaboration between the architect and builder

In the case of Yokoso, you were the first one at the table but are there situations where the client, architect or builder are bringing you in as the third party?

Yeah, that’s way more common. That’s typical for us as designers to get brought in when there’s already a team in place.

I feel like the best collaborative environments are where everybody – contractor, architect, designer – are all open to looking at other people’s proposals and study things again without taking that personally.

My favorite and the most productive meetings are when we have client, contractor, designer and architect all sitting at the table together working on concepts. I can propose things that just don’t work. When it comes to equipment, HVAC, code, I’m not well-versed in those. To have an architect and contractor team there to look at all of the parts that I might have blinders on, I feel like gives us all some guideposts in terms of how we can make things work so that the likelihood of any of us proposing something that’s completely impossible is going to be drastically reduced.

How does your design intent relate to value engineering?

Those are two different parts of the process to me. I talked a little bit about how we start out with the concept in its entirety. I’m sourcing materials, defining finishes for me that’s what I call a design intent package. That’s one of the missing components that we provide to people that aren’t necessarily in place when you have an architect package, a permit set, anything like that where you go straight into construction. We have a design intent set, so that shows materiality. It also shows visuals of the space. I’m learning more in the past couple of years that that even helps contractors on site do their work when they can just see. Instead of just a CAD drawing, they can look at that visual and say “Oh that’s how it’s supposed to look.” That’s been a really nice tool. It’s also a nice tool with clients so they can understand prior to building out a space what it’s supposed to look like.

Value engineering comes into play when cost starts to come into play. You look at where your cost is versus where you want it to be and then you take that design intent package and say “How can we take this intent and change some of the material?”

An example: some of the ceiling materials in Yokoso had changed from a corrugated plywood, wavy material across to a different acoustic material that we found. Some of the concrete-look materials went to a laminate instead of an actual concrete. Things like that saved a lot of money, and in the long run, aesthetically, we’re really happy with how it all came out. In fact, some of those things become advantageous. You’re quickly working through a design process; you’re specifying things you know will look good. There’s a stage where you get into value engineering where you really hone in on some big ticket items and start asking yourself, “Is this necessary?” If we need to re-do it, how do we re-do it and still create a similar look and bring down cost? For the ceiling elements in Yokoso, for example, we got to add acoustical properties in that. That turned out to be a win-win situation for everybody

Design intent is something that we all try to stick to as we’re working through the build process. Value engineering historically has a bit of a negative connotation because that’s where you have to cut costs, but I think that it’s about shifting perspective. That can also be a major opportunity to make conscious, good choices that possibly make it turn out even better than it was before.

Compton + Sidecar Creatives

Oftentimes if I’m specifying a flooring material, I’m not digging for the price. I’m talking to reps, looking at low, mid, high range but I don’t know the actual cost, but Compton will come in and line item those types of things out so I can sit down and say “Okay this is a big chunk of money, is there something that we can do here? Is there a material swap there?” So Compton is a huge help there.

But being so close to you guys and having a working relationship also comes into play earlier. Compton has ideated with me. Compton has shown me materials that I’m not aware of. There’s all kinds of collaborative ways that having a close relationship with my preferred contractor has helped me as a designer. It’s been one of the best decisions ever to have such a close relationship with Compton and some of the team members. We now have a pretty good handle on how the other team works and we’re able to streamline our processes and help each other out along the way.

Tags: bri derolph, sidecar creatives